THE ANONYMOUS

People are obsessed with the time and the weather. We’ve talked about the weather since we were all cave dwellers hunting with spears. But the time is a different matter. Sure, people always had the idea of the passage of time. The sun rising and setting gives a natural sense of days, but daylight and dark periods vary by the time of year and to get an accurate and linear representation of time turns out to be rather difficult. That is unless you are a Greek engineer living in Alexandria around 250 BC.

Legend has it that and engineer working in his father’s barbershop led him to discover not only the first working clock, but also the pipe organ, launching the field of pneumatics in the process. That engineer was named Ctesibius and while his story is mostly forgotten, it shows he has a place as a historical hacker.

Legend has it that and engineer working in his father’s barbershop led him to discover not only the first working clock, but also the pipe organ, launching the field of pneumatics in the process. That engineer was named Ctesibius and while his story is mostly forgotten, it shows he has a place as a historical hacker.

You might think there were timekeeping devices before 250 BC, and that’s sort of true. However, the devices before Ctesibius had many limitations. For example, a sundial can tell time, but only if the sun is shining. At night or during a storm it is worthless.

The Problem with Water Clocks

One early way to measure time was the clepsydra. This is essentially a pot with a spout near the bottom that you can close with a bung. The Greeks used these for, among other things, giving lawyers on both sides of a debate equal time. A timekeeper would fill the clepsydra to a mark and remove the bung. Your time ran out when no more water came through the spout. If there was a recess, the bung could pause the timer.

This kind of clock has been around for many years and in many ancient cultures. China may have had them as early as 4,000 BC and India possibly around 2,500 BC. Egypt developed them somewhere around 1,400 BC.

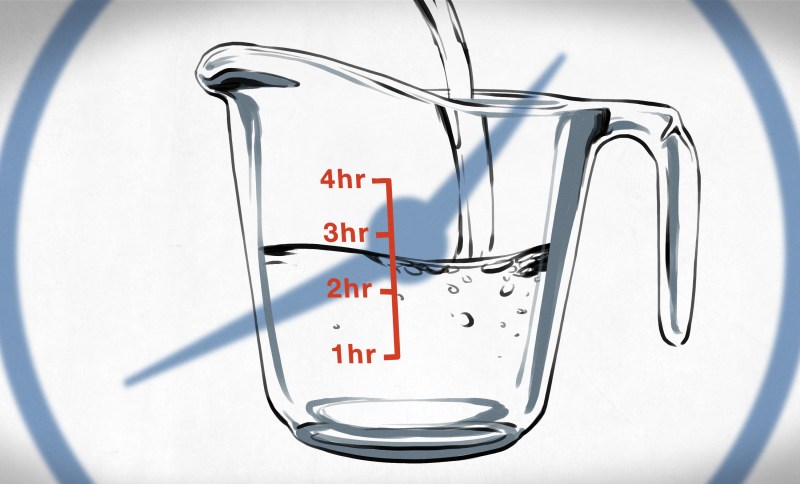

The problem with the clepsydra is that more water comes out when it is full than when the pot is nearly empty. So while it works to make sure everyone gets the same amount of time, you couldn’t, for example, time three people by letting one clepsydra fill a cup with water. The first cup would fill faster than the last cup due to the changing water pressure in the vessel.

Ctesibius worked in his father’s barbershop — that’s the modern parlance since we don’t know what they were really called in 200 BC Alexandria. Apparently, there was quite a bit of dripping water in the shop. The dripping water gave him an idea and the result was a series of clocks that would remain the most accurate clocks in the world until the pendulum clock appeared in 1656.

How it Worked

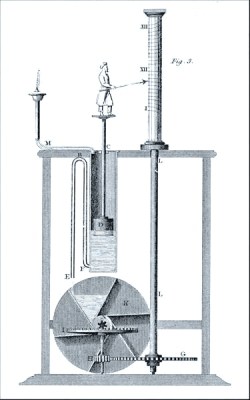

While a normal clepsydra has a fixed amount of water, Ctesibius’ version had a larger source of water above it. It would fill the lower vessel faster than the spout drained water. In addition, the lower vessel had an overflow sluice so that excess water would runoff.

While a normal clepsydra has a fixed amount of water, Ctesibius’ version had a larger source of water above it. It would fill the lower vessel faster than the spout drained water. In addition, the lower vessel had an overflow sluice so that excess water would runoff.

Because the top vessel fills the lower vessel faster than the water exits, the lower vessel stays full all the time — at least as long as the upper vessel isn’t empty. Because the lower vessels’ pressure stays constant, the flow of water from the spout also stays constant, meaning you can measure time linearly. For example, collecting the water from the spout in a third vessel with a float will tell you how long the clock has been running. If the float takes 10 minutes to rise 1 inch, then an hour is 6 inches.

While these clocks were considered accurate in their day, they weren’t by modern standards. In particular, the viscosity of water affects the accuracy of the clock. Water’s viscosity can change a few percentage points with each degree of temperature change. Freezing water won’t work at all. There’s no evidence that ancient water clocks regulated their temperature, so the clocks were probably not very accurate. However, these clocks were reset when refilled — a common occurrence — so at least the errors did not accumulate. You can presume they were reset to something like the sunrise or a sundial.

Lost to Time

Ctesibus apparently understood something about water pressure and also worked with compressed air. But the depth of his understanding and resulting inventions is a mystery. The very little we know about Ctesibus is through mentions of him in other works by Vitruvius, Athenaeus, Hero, and others. His works were mostly lost, probably in the fire at Alexandria.

Want to try your hand at making ancient clocks? Try the video below. Or try a more modern take on the water clock. If you want to see how far we’ve come, [Bill] has a good explanation of atomic clocks which are about as far from a clepsydra as you can get.

from Hackaday https://ift.tt/3543DwN

Reviewed by HA TECH

on

June 09, 2021

Rating:

Reviewed by HA TECH

on

June 09, 2021

Rating:

No comments: